Perhaps the greatest sense of pedagogical innovation and challenge of my course is the desire to offer differentiated pacing. The last few years, my flipped course has been asynchronous.

One on hand...

It's been a great experience. Students have learned to become more responsible for their learning and self-directed. Asynchrony has also allowed students to slow down when they struggle with the content and speed up during other times. This has given me an opportunity to work with individual students on their particular needs. Excelling students can learn content beyond the scope of my course if they finish the course or particular units quickly. Struggling students no longer have to worry that their questions or misconceptions are slowing down the rest of the class.

On the other hand...

I've found in past years that the majority of students who work from behind are due to time management and motivational issues, rather than profound challenges with the content. The reason for moving to an asynchronous class is to allow students to learn at the speed which helps them learn most effectively. Unfortunately, while asynchrony has benefited the excelling and struggling students achieve this goal, it has been a struggle for some of the middle students with executive functioning and motivational issues. In essence, I've given these students the opportunity to slack off. In a synchronous class, these students would have been forced to learn more.

Another issue is when students are learning and struggling together, it bonds them in an inspiring way. It creates a class culture that is hard to recreate in an asynchronous class.

On both hands...

Last year I made a conscious effort to recreate some of the synchronous experiences in the asynchronous setting. Students responded to warm up and exit ticket prompts in their journals at the beginning and ending of lessons. We played formative assessment games and did peer instruction at the beginning of other lessons. Students planned out their week at the beginning of Mondays and reflected about their week last thing on Fridays. These were helpful strategies to develop student metacognition. But I've found this year's cohort do not require the same level of reflection and for the most part can handle the content with ease. Therefore, these ideas are not as helpful.

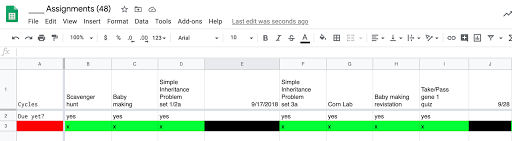

This year, I've made some changes that I hope will better serve these students. Rather than giving away complete autonomy of pacing, my suggested course calendar represents the slowest speed allowable. Students have permission to move ahead but cannot fall behind. After students fall behind beyond a time frame (every 8 days), I send home academic notifications. When it becomes obvious that a student is in jeopardy of falling behind, I try to send a warning email to the student prior to sending home a notification. Since students are no longer required to map out their week, I do not start Monday's with the planning activity. In fact, I try to give the students as much asynchronous time as possible since I'm holding them more accountable to work at a certain pace. This also means doing away with the journaling. Instead, I've been more strategic about how to use synchronous times in class.

So far, I've kept the formative assessment games and peer instruction when it appears necessary based on how well the students are grasping the material. In addition, I've reinstituted the Socratic seminar discussions. Perhaps I hastily gave up the seminar discussions last year - they are a true joy. They breathe a life into the class that was missing last year. Students report enjoying the discussions because they find the articles and controversial issues interesting. They also enjoy switching to full class activities once in awhile. To facilitate optimal engagement, I give students a heads up of the scheduled date for the seminar and encourage students to be ready to talk by that date.

The final synchronous exercises I've reinstituted is the full class exam and common due dates for lab reports/write ups. As I predicted in a previous blog article, these deadlines have helped keep students accountable for pushing through the curriculum at a reasonable pace. The biggest deadline is also at the end of quarters; students must earn level 3 on specific "I can" statements by the end of the quarter.

I'm hoping the suggested pacing calendars and the synchronous scaffolds of quarter, semi-weekly, test, lab report, and full class discussion deadlines will provide enough structure and accountability in my asynchronous course to help students who need traditional elements of schooling. I also hope that these attempts of support will still allow students to learn at their own pace instead of being rushed through the curriculum. In essence, I hope I'm successfully straddling the synchronous-asynchronous line.